On a brisk February evening in 1922, the Brookline Board of Selectmen met with son of Central Park’s famed designer to discuss beauty. More specifically, the selectmen met with Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., an early leader of the City Beautiful movement, to discuss how to protect the beauty of their leafy suburb from commercial eyesores. Local homeowners – the professional children of Boston’s old “Brahmin” mercantile class – were getting worried.

Under the watchful eye of Boston’s foremost nepo baby and zoning reformer, nervous Massholes authored some of the earliest suburban zoning by-laws, dividing their town into business, local store, and general residence districts and banning commercial construction from the last. Almost immediately, similar meetings were called in similar towns.

These meetings weren’t all about billboards, but they were mostly about billboards1. In 1910, there had been 458,000 automobiles on American roads. That number was spiking – by 1930, it would sit at 23 million. For advertisers, all that driving presented an opportunity. By 1922, there were roughly half a million billboards nationwide – one every third of a mile along major routes.

Long before smartphones, cars collapsed time and space – and held consumers captive for advertisers. What began in Brookline as a fight over views of the fens became the first panic over the attention economy. Olmsted Jr. and his selectmen didn’t just scramble to write by-laws; they scrambled to articulate the moral logic behind them. That logic, unstated but well defined, endures today as ersatz digital zoning – class dependent experiences of marketing that flatter professionals into thinking they’ve retained control of their attention. Algorithmic reinforcement, data policies, and premium upsells maintain this illusion, making the digital world feel at least a bit like a leafy suburb to those who might otherwise take action.

This wasn’t hard to see coming. Today, real-estate listings for some of Brookline’s grandest homes brag about views of the CITGO sign – a 60-foot-tall ad for a company once majority-owned by the Venezuelan state oil firm PDVSA that looms just across the town border. It’s a literal landmark, the bell tower to Fenway Park’s cathedral.

It’s also, as they say, a faahking billboard.

Initially, anti-billboard reformers focused on nature. More specifically, they focused on views of nature. The poet Ogden Nash2, writing in The New Yorker, captured their argument in verse: “I think that I shall never see / a billboard lovely as a tree. / Indeed, unless the billboards fall, / I’ll never see a tree at all.” But anti-billboard reformers didn’t just care about nature. That was simply the language closest at hand – all those John Muir paeans to the beauty of the West. Back East in Brookline and Scarsdale and Winnetka, “horizon” talk didn’t quite play. So organizations like the National Roadside Council expanded their vocabularies to encompass the concerns of the people who donated to the National Roadside Council. NRC founder Elizabeth Boyd Lawton declared that “We must make our choice between beauty and the billboard.”

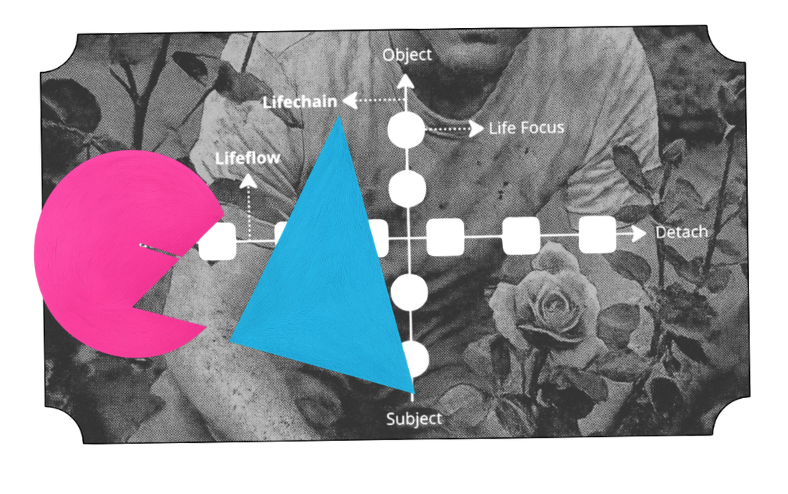

That framing suggests that the choice made will reflect a deeper truth about the ones who make it; either we’re human beings engaged in periodic acts of commerce or commercial beings engaged in periodic acts of humanity. Obviously, we aspire to be the former. But it’s a struggle.

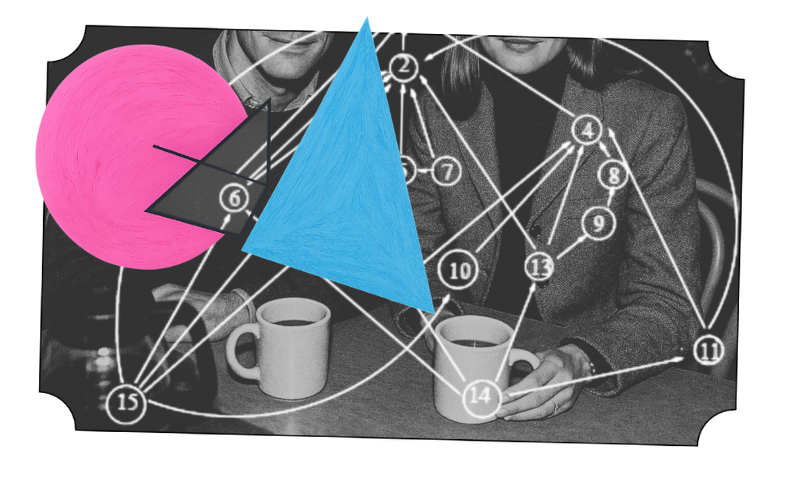

That struggle continues, specifically among self-consciously “conscious consumers” who abhor having their sightlines blocked by commercial vulgarities so much they experience that intrusion as a form of status injury. Offline, that often results in NIMBYism. Online, it results in what the modern Ogden Nash, New Yorker reporter Kyle Chayka, calls “algorithmic self-doubt.” When our Instagram pages populate with ads for weight-loss gummies, wine-mom tees, Temu slop, pay-later apps, and drop-shipped gadgets, we wonder if we haven’t settled in the wrong digital neighborhood. We worry about the value of our attention decreasing in precisely the same way a bunch of dead Brookliners worried about the value of their land.

Sociologist Minna Ruckenstein describes this quest for aesthetic self-determination as “co-evolving with algorithms.” Educated users click strategically to signal who they are and what kind of attention they deserve. The goal is not to find better information but to exert self-control—to choose beauty.

We are given that choice.

We – those with political clout and economic leverage – are given that choice because large corporations understand that the consequence of not giving us that choice would likely be legislation.

In 1934, the Outdoor Advertising Association of America declared a new policy of “self-regulation to protect natural beauty.” The OAAA hadn’t lost enthusiasm for big rectangles; its leaders were concerned about the passage of laws banning billboards. Their new policy permitted members to continue putting up ads in commercial districts (read: poor areas) while strongly suggesting leaving the lawyers in Scarsdale alone.

In 2021, Apple pushed its iOS 14.5 privacy update, which limited cross-app tracking. The effects were felt immediately by DTC brands like Casper, Allbirds, and Blue Apron that had been spending enormous sums – often 25 to 35 percent of revenue – on targeted Facebook and Google ads. Their performance dipped, so their spending dipped, allowing smaller, more differentiated DTC brands to squeeze onto various social platforms, where they felt more like content and less like billboards. A few years later, as spam calls got crazy, Apple introduced its “Ask a Reason for Calling” feature (check your settings) to screen for cold callers.

Apple pitched its updates as user-friendly – and they were. But they were user-friendly in service of a goal: avoid legislation. Just as the OAAA cleaned up its act to avoid being forced to really clean up its act, Apple cleaned up its act to avoid having its hand forced by legislators wholly uninterested in its margins – legislators eager to publicly choose beauty because they liked the optics.

The result of corporate self-regulation and consumer self-curation is the creation of protected digital neighborhoods where value accrues to those who already own the attention3. The big emphasis among attention-seeking tech businesses (think: streamers) over the last few years has been the creation of tiers. When companies can’t monetize using ads, they monetize by offering ad-free service. YouTube does. Spotify does. Netflix does. Disney does. On and on. Premium means beauty means self-control means no ads.

Brookline followed a similar trajectory. By the mid-century, it had extended its zoning logic into an outright ban on off-premise billboards entirely. What began as Olmsted’s genteel land-use map had hardened into a firewall. No rectangles. Just the one triangle.

The result was that Brookline got more expensive – not just to buy in, but to live in. It became premium and expectations ramped up. Residents added onto their homes. The beautiful homes themselves became more than just beautiful homes; they became advertisements to upgrade. It’s a familiar dynamic. When content companies want to drive premium upgrades, they program content that appeals to people who hate advertising. The result is that those upmarket users start to experience content as advertising and vice versa. Thus Frankenstein on Netflix. Thus The Lowdown on Hulu.

Thus every single thing on Apple+.

For the last hundred years – ever since the great billboard panics of the 1920s – the ethos defined by Olmsted Jr. and his cronies has persisted: Not in my neighbor’s neighbor’s neighbor’s neighbor’s backyard. So-called sophisticated people are led to believe that they can choose beauty. But that’s only true to the degree that the people who command their attention allow it to be true – the degree to which it’s in their economic best interest.

Ostensibly, Brookliners saved themselves from billboards. Actually, by focusing on intrusive advertising – attention, really – as a local rather than national issue, Brookliners saved billboards from themselves. Convinced they’d chosen beauty, they let the world get uglier. They were protected by their own political and economic power, but because they didn’t use that power to protect others they wound up paying extra to have an unobstructed views of the CITGO sign4.

[1] These meetings were also about garages. The vast majority of building permits issued at that time in American history were for garages, which makes perfect sense if you think about it.

[2] Ogden is a good name. How have I never met one in Brooklyn. Makes no sense to me. “This is Oggy.” I love that. (Granted, I do know two Augies.)

[3] See Netflix. Or, better yet, try not to see Netflix.

[4] Okay. So. Big Red Sox fan. Feel uncomfortable hating on an icon. But here’s the thing: It’s only special because we made it special. We could have made something more beautiful special. It could be an obelisk honoring Spaceman Lee for being the most drugged out professional athlete in history. IDK. Something else.