In 1921, the Pulitzer Prize jury for fiction selected Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street, but the Pulitzer Board vetoed the choice. The board, led by Columbia University president Nicholas Murray Butler, claimed that Lewis’s satire of small-town intransigence was acidic, cynical, and therefore an inappropriate choice for a prize that – at that time – was supposed to be awarded to books celebrating “the wholesome atmosphere of American life and the highest standard of American manners and manhood.”

Main Street portrayed provincial Americans as vicious and parochial, so the Board gave the prize to Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, which portrayed New York’s urban elite as vicious and parochial. The irony wasn’t lost on Lewis and Wharton, who thought of themselves as participants in the same project. Both sought to honestly capture the material circumstances, social mores, and hypocrisies of Americans – different kinds of Americans, sure, but Americans all the same.

“The greatest mystery about a human being,” Lewis wrote in Main Street, “is not his reaction to sex or praise, but the manner in which he contrives to put in twenty-four hours a day.”

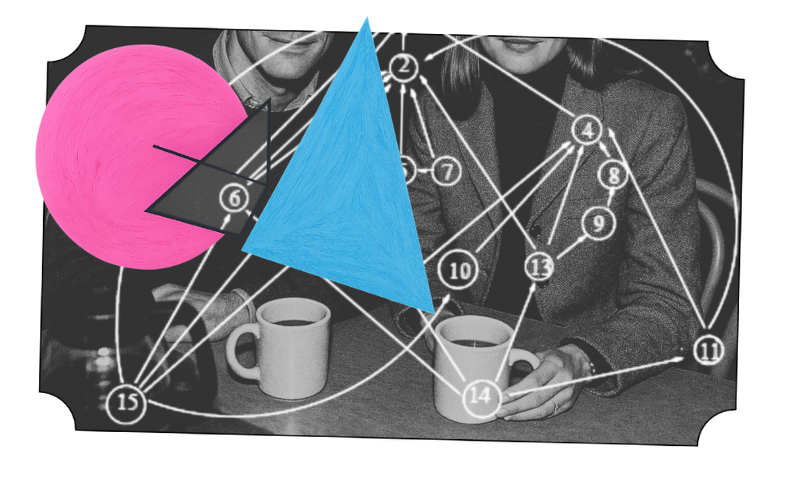

Increasingly, the current equivalents of Wharton’s decorous, two-faced urban elites are changing how they “put in twenty-four” by heading for Main Street. They are starting or buying small companies. They are leaving large ones1. Though coverage of the “Great Resignation” stopped in 2022 and the narrative has turned toward “job hugging,” the exodus never really ended. Through 2024 and into 2025, roughly 3 million Americans a month quit their jobs – well above pre-pandemic norms. Gallup surveys show nearly 60% of workers describe themselves as psychologically detached. Even within glassy downtown skyscrapers, what looks like quietude is often the prelude to a resignation, and many firings are justified by total disengagement.

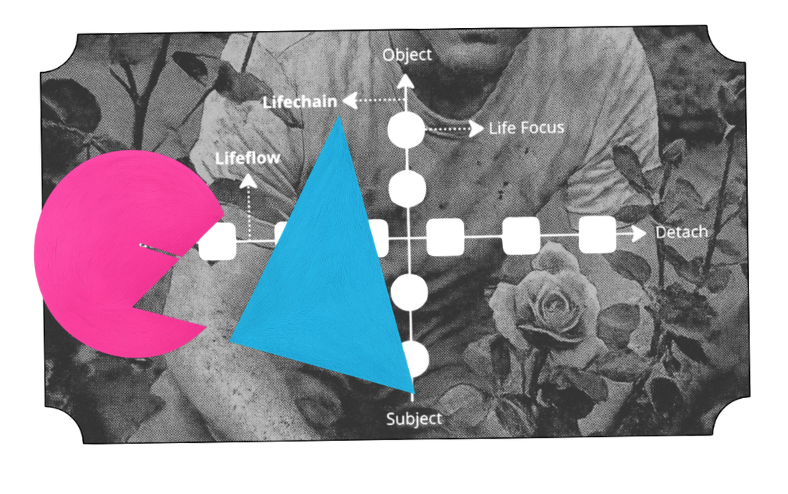

It’s tempting to characterize highly credentialed corporate defectors as “downwardly mobile elites,” but that misunderstands the historical context, the elite demimonde, and Main Street itself. These people aren’t sliding down; they’re moving orthogonally across a plot of personal values, away from institutionalism and consumerism (the things you can get a Pulitzer Prize for mocking) toward individualism and thrift (the things you can’t). The bottled elite—all those Slack users—are spraying out into the world with force. It’s a messy, uncontrollable process, but it’s a mistake to assume that temporary chaos will lead to lasting disorder. It won’t.

The Age of Innocence is set in the 1870s, which is more or less when elites got bottled in the first place. In the late nineteenth century, America rapidly transformed from a patchwork of self-reliant communities into a nation of bureaucracies, professional associations, and corporations. The scholar Robert H. Wiebe described this as the “organizational revolution.” The thing that got overthrown was American self-reliance. This became an institutional country with a stronger national identity rooted in national organizations and organizational hierarchies2.

The Plot of Personal (American) Values

Upper Middle is a member-supported publication. Want access to the data and analysis that has helped 5,300+ anxious professionals re-negotiate their relationship with status, taste, and money?

Already a member? Sign In.

➺ Weekly research-focused "Class Notes" essays looking at learned behaviors, cultural/social biases, and internalized expectations.

➺ Biweekly survey data-driven "Status Report" teardowns of why people like us act like this. (Future state: Access to raw data via AI portals.)

➺ Invitations to "Zero-Martini Lunch" live Q+As with scholars, authors, experts and minor celebrities with insight into the Upper Middle lifestyle.

➺ Other stuff. Access to deals. Introductions…. We're always trying shit.